The Gret Flodes!

- Posted in:

- Archaeology

- NewsletterArchive

This wonderful articles comes from our Spring 2001 newsletter:

It was the ‘gret myte water flodes’ which in 1495 were recorded to have destroyed Newark Castle Bridge. Similarly, in recent times, we have experienced many destructive floods in the county. Media hype tends to portray floods as freak events when in reality they are a quite usual, albeit devasting, occurrence.

It was in 1336, for example, while riding through the fields of Hoveringham on a crippled horse (which would have been a disadvantage at the best of times), that the unfortunate Robert Glover met his untimely death when the ‘waters of the Trent having greatly overflowed, he could not see his way and fell into a certain hole and was drowned’. The flood of 1795 was recorded as ‘the greatest flood ever remembered by the oldest person living’, ‘so awful, so sudden a visitation, worked upon the feelings of all descriptions of people; the rich and the poor, in different places, were all alike involved in the general catastrophe’.

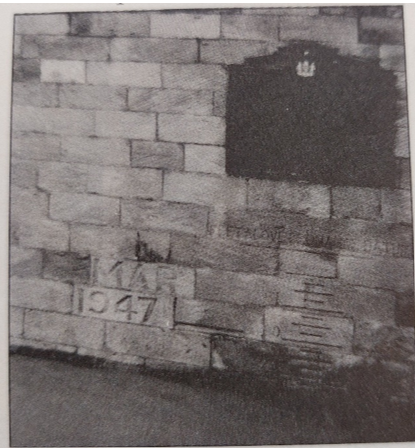

Above: The peak levels of major floods are recorded at Trent Bridge; against this we can see just how high the water rose in November 2000 during a flood.

As these historical accounts suggest, flooding of the Trent has always happened. We also have a growing body of archaeological evidence for these episodes stretching back into the distant past.

When the Trent floods over its banks it leaves silty deposits stranded beyond the river when the water retreats. Layers of this material, called alluvium, have been found at several sites. At Besthorpe quarry, excavations have dated these to suggest a period of flooding in the middle Bronze Age, while at the Roman town of Segelocum at Littleborough, at least two phases of flooding and river deposits have been found interleaved between phases of Roman building.

The Trent also has more severe but less frequent ‘catastrophic’ floods that can be of sufficient force to alter the course of the river. This leaves behind a series of redundant river channels, called palaeochannels, and these have yielded interesting evidence of flooding. At Colwick Hall quarry, a palaeochannel was found to contain numerous large tree trunks which would seem to have been uprooted and deposited in successive huge floods. These have been dated by dendrochronology (tree rings) to the Neolithic period (approx. 5000-2500 BC). At Langford quarry, human remains dating to the late Neolithic have also been found in a palaeochannel. These were either the victims of a flood or the water washed out remains from a burial site.

Archaeological evidence of flooding can also be seen in man’s reaction to these events. One human response to something so devasting is to call upon the mercy of the Gods. It is argued that the sudden increase in deposits of Bronze Age metalwork found in river silts may be evidence of these kind of appeals. A more practical response can be found in the system of major and minor flood defences. These were built to protect towns, villages and farmland and could have a significant impact on the local landscape. Unfortunately, many of these features remain undated.

Archaeological and historical accounts not only help us understand flooding in the past, but can be used to draw useful anecdotes as part of an informed and effective modern-day approach to this phenomenon.