Inventions from Nottingham: The Stocking Frame

- Posted in:

- Heritage

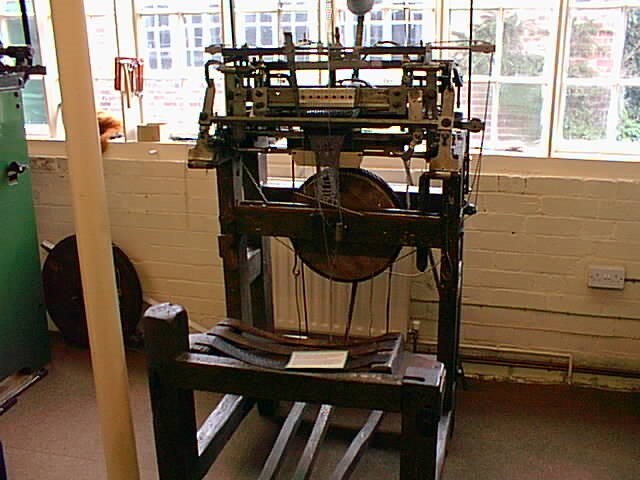

One invention that is thought to have originated out of Nottinghamshire is the Stocking Frame. The stocking frame, invented in 1589, was a revolutionary knitting machine used within the textile industry. The use of this machine helped bring about the Industrial Revolution and the principles of machine knitting laid out by this machine are still used in the textile industry today.

Its invention is attributed to an Englishman named William Lee. Sadly, nothing much concrete is known about William. Most reports theorise he was a clergyman from Calverton, Nottinghamshire. There has been some argument that he lived in Sussex instead, but scholars predominantly believe he was a Nottinghamshire man. We are inclined to agree!

The stocking frame worked by imitating hand-knitting movements. It was unlike anything available at the time. Lee sought out a patent for the machine from Queen Elizabeth I. Upon demonstration of the machine, Elizabeth declined his patent request on the fear that his machine would be highly detrimental to those working in the hand-knitting industry. Elizabeth promised William that if he could improve his machine to be able to make silk stockings then his patent would be approved (Rowlett 1886).

His machine wasn’t a perfect invention from conception. The frame originally could only produce coarse fabrics as it contained eight needles in an inch. So, William worked on improving the machine, by increasing the needles per inch, until, in 1598, it was capable of knitting silk stockings.

Above: Stocking Frame at Framework Knitters Museum, Ruddington, Nottinghamshire. By John Beniston (Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0).

Unfortunately for William, despite his improvements, his patent was declined again by Elizabeth’s successor James I. Upon this rejection, he decided to take the stocking frame and his workers to France under the protection of King Henry IV.

In 1610, however, Henry IV was assassinated. At a time where religion was a very divisive aspect of society, the death of the Protestant King Henry and the succession of the Catholic Louis XIII had consequences for the Protestants in France. As one of those Protestants, William’s stocking frame business badly suffered. William died in Paris a few years later (many report that he died in 1614) with his business that he had worked at for decades in disrepair.

Some of his stocking frames made their way back to England with his workers. Many workers sold their frames in London while his brother James is reported to have helped to establish the use of the stocking frame into the textile industry in England.

In the seventeenth and eighteen centuries, the stocking frame ‘was probably the most sophisticated textile machine in common use in western civilisation’ (Lewis, 1986). The frame could hold around 38 needles per inch by 1750 (Lewis, 1986), a stark difference from the number of needles on the initial conceptions of the machine. By the mid-seventeenth century , attempts were made by framework knitters to ‘regulate the exportation of machinery and skilled labour…as a reflection of the workers’ new-found estimation of his machinery and skills’ (Lewis, 1986).

Further adaptions of Lee’s machine continued even up to the 19th century as the stocking frame was adapted for different textiles and knitting styles. By the start of the 19th century, the machine had notably been adapted as a lace making machine, which also has special connections to Nottingham in the form of the lace market.

Lee most likely had no idea how much of an importance his machine would have on the textile industry centuries down the line. His influence ‘laid the foundation for an industry that now gives employment to millions. There can be but few people in the world who do not make daily use of its products’ (Pasold, 1975).

If it weren’t for the dedication and determination of Lee and his loyal workers to continually improve the stocking frame, the history of textile production would look wildly different.

If you would like to learn more about the stocking frame or about the textile industry, we suggest you visit the Framework Knitters’ Museum in Ruddington.

Bibliography:

Pasold, E.W. 1975. ‘In Search of William Lee’, Textile History, Volume 6. Pp.7-17

Rowlett, W.T. 1887. ‘Framework Knitting’, Journal of the Society of Arts, Volume 36. Page 445